Benjamin Stora gave an interview with Kersten Knipp published on Qantara.de as "The Bitter Legacy of Past Franco-Algerian Relations" on March 4, 2011 (and apparently translated from German to English - does Stora speak German?). Stora expounds upon France's reluctance to remember the loss of Algeria and Algeria's use of this history to legitimize their country today. I copy a snippet of the text below:

Knipp: France and Algeria have completely different memories of their common history. How would you characterise these memories?

Benjamin Stora: For a long time – for almost 30, 40 years – France primarily fostered a culture of forgetting. People didn't speak of Algeria; they wanted to put that era firmly behind them – the war and, of course, the defeat, the ignominy of ultimately having to withdraw from Algeria. After all, the French considered this North African nation to be an integral part of their national territory.

The Algerians, on the other hand, were faced with "too much" history. For them, it was about a memory that they could use to legitimise the existence of the nation and, above all, political power, which they tried to legitimise through heroic stories.

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

Pied-Noir and pro-Arab, from the Minorités Review

Didier Lestrade wrote, "Pied-Noir et pro-Arabe" on Feb. 20 for the Revue Minorités, in which he reflects on the current political situation in Egypt, Libya and other so-called "Arab States." His take on the Pieds-Noirs, in which he includes himself, is worth sharing without comment. I have excerpted the essay and my translation to English follows the original text.

* * *

J’ai 53 ans, je suis pied-noir et fils de pied-noir. Or, tous les pieds-noirs que je connais sont heureux de ce qui se passe dans ces pays, mettant de côté mauvais souvenirs et drames. Même mes parents sont sincèrement heureux. Et je me dis que la dernière génération de pieds-noirs à laquelle j’appartiens devrait manifester sa joie et l’imposer à l’autre partie des pieds-noirs, plus âgée, celle qui truste les associations et les leaders politiques, celle qui empêche littéralement la France de sortir de cette rancœur vis-à-vis des arabes. À cause d’eux, l’Algérie souffre toujours, à cause d’eux on ouvre des musées qui glorifient le colonialisme et on vote des lois qui lavent leur conscience. À cause d’eux, la classe politique française ne peut dépasser le traumatisme de l’indépendance et accompagner le développement des autres départements français qui souffrent encore du colonialisme comme les Antilles. C’est toute une chaîne de blocages qui est entretenue par les anciens pieds-noirs.

[...]

Nous sommes la dernière génération de pieds-noirs, il n’y en aura pas d’autre après nous. Nous sommes nés juste avant ou pendant l’indépendance et nous n’avons pas à payer pour les erreurs de nos parents et de leurs familles. Mais, en fait, nous avons déjà payé toute notre vie leur influence. Notre amour de nos racines n’a pas pu être exprimé à cause de ces origines dramatiques. Nous n’avons pas pu développer de vraies amitiés et de vraies histoires d’amour avec des arabes car le poids des morts reste entre nous. L'immense majorité d’entre nous n’a pas eu le bonheur de retourner sur son lieu de naissance et c’est le moindre des prix à payer pour l’histoire. En France, tout le monde a le droit de retourner dans la ville de naissance, sauf nous. Vous réalisez ce que ça veut dire ? Nous nous sommes sacrifiés car nos parents refusaient de s’excuser une bonne fois pour toutes comme cela s’est passé dans tous les pays colonialistes de manière à passer, enfin, à autre chose.

Ces vieux pieds-noirs nous empêchent de vivre. Ce sont de mauvais parents puisqu’ils imposent un état de fait à leurs enfants qui payent le prix de la bêtise obstinée des anciens. Et ce qui se passe aujourd’hui dans les pays arabes les met encore plus dans une position fautive. Que faut-il penser ? Que la France ne s’excusera jamais devant l’Algérie tant que le dernier pied-noir d’extrême droite ne sera pas mort ? Mais qu’il meure alors ! Qu’on l’enterre plus vite ! Pouvons-nous nous permettre d’attendre encore 10 ou 20 ans alors que la démocratie arrive dans les pays où elle n’a jamais été envisagée parce que nous-mêmes ne l’avons pas apportée ? Allons-nous perdre toute notion de proximité avec les pays arabes alors que nous les connaissons mieux que les autres ? [...]

* * *

I’m 53, and I am a Pied-Noir and the son of a Pied-Noir. And all of the Pieds-Noirs who I know are happy about what is happening in these countries, putting aside the bad memories and drama. Even my parents are sincerely happy. And I think that the last generation of Pieds-Noirs, to which I belong, should demonstrate its joy and impose it on the other, older Pieds-Noirs, those who monopolize the associations and who are the political leaders, those who literally keep France from getting over this resentment towards the Arabs. Because of them, Algeria is still suffering, because of them, we open museums that glorify colonialism and we vote for laws that clear their conscience. Because of them, the French political class cannot get past the trauma of independence and join the development of other French departments that are still suffering from colonialism, like the French Caribbean. It’s a whole chain of blockages that is kept up by the old Pieds-Noirs.

[...]

We are the last generation of Pieds-Noirs, there will never be another after us. We were born just before or during Algerian Independence and we do not have to pay for our parents’ mistakes or the mistakes of their families. But, actually, we have already paid our whole lives for their influence. Our love of our roots could not be expressed because of these dramatic origins. We could not form true friendships and true love stories with Arabs because the weight of the dead remains between us. The vast majority of us have not had the chance to return to our birthplace and this is the least of the prices to pay for history. In France, everyone has the right to return to the town where they were born, except for us. Do you realize what that means? We sacrificed ourselves because our parents refused to apologize once and for all for all that happened in the colonial countries in a way that would let us move on to something else.

These old Pieds-Noirs are keeping us from living. They are bad parents because they impose this situation on their children who pay the price for the obstinate stupidity of the elderly. And what’s happening today in Arab countries makes them even more culpable. What should we think? That France will never apologize to Algeria as long as the last Pied-Noir from the extreme Right isn’t dead? Well let him die, then! And let’s bury him as quickly as possible! Can we allow ourselves to wait another 10 or 20 years so that democracy can arrive in countries where it had never before been imagined because we didn’t bring it there ourselves? […]

Sunday, January 30, 2011

unexpected loss of homeland

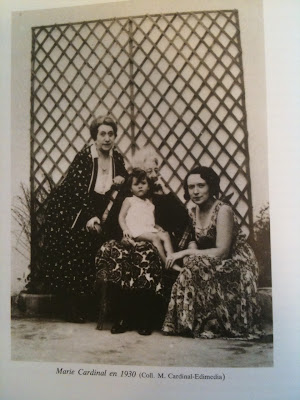

While I work on articles related to hoarding memories of the homeland and the links between collecting memorabilia and writing the self, I have come across a poignant passage from Marie Cardinal's Les Pieds-Noirs (Belfond, 1988) in which she speaks about her unexpected loss of home. I quote here the original followed by my translation.

Les années d’insouciance, celles de mon enfance, de mon adolescence, et les premières années de ma vie de femme… les premières amours…le premier enfant… Le poids de cette légèreté, de cette beauté, de cette tendresse, de cette inconscience ! Peut-être que cela palpite toujours en moi parce que je n’ai jamais quitté ces images pour toujours, jamais je ne les ai rangées dans un tiroir ou une valise, jamais je n’ai regardé la terre de ma jeunesse en me disant que je n’y serais plus chez moi. La dernière fois que j’en suis partie, je ne savais pas que c’était la dernière fois. J’étais venue de Grèce où j’enseignais au lycée français de Thessalonique. Enceinte de huit mois, incapable de voyager en avion dans l’état où j’étais, j’avais méandré soixante-dix heures à bord de l’Orient-Express qui prenait des allures de diligence, puis j’avais vogué vingt heures sur un paquebot, pour venir, comme une tortue, mettre au monde mon enfant sur mes plages. Je n’imaginais pas qu’un petit venu de mon ventre puisse voir le jour ailleurs que là… Ensuite je suis repartie avec ma fille dans mes bras, c’était l’été, je reviendrais pour Noël. Je ne savais pas que, désormais, je n’aurais plus de maison. Je ne savais pas que ma terre ne serait plus jamais ma terre. (11-12)

The carefree years, those of my childhood, my adolescence, and the first years of womanhood ... first loves ... the first child ... The weight of this lightness, this beauty, this tenderness, this unawareness! Perhaps it still pulsates in me because I never permanently left these images, I never put them away in a drawer or a suitcase, I never looked at the land of my youth while telling myself that I would never again be home. The last time that I left, I didn't know it would be the last time. I had come back from Greece where I was teaching in a French high school in Thessaloniki. Eight-months pregnant, unable to travel by airplane in that state, I had meandered seventy hours aboard the Orient Express that ran at the speed of a stagecoach, and then I wandered twenty hours on a steam ship, so that, like a turtle, I could give birth to my child on my beaches. I couldn't imagine that this child coming from my tummy could ever see the day somewhere other than there... Then I left again with my daughter in my arms, it was summer, I would come back for Christmas. I didn't know that, from then on, I would no longer have a home. I didn't know that my land would never again be my land.

Her lightness of being, her state of carefree existence, came from knowing her home would be there to support her. Once it was gone, she attached herself to the mental image and repeated it throughout her literary career. Les Pieds-Noirs is a photographic coffee-table book mixed with autobiography and history of the Pied-Noir people. It is, in many ways, a reproduction of the lost homeland, a surrogate and horribly insufficient space designed to protect the past from being forgotten.

Sunday, January 23, 2011

Remains of the St Eugène Cemetery

Return voyages almost always include emotional visits to cemeteries, representative of lost lives, ancestries, absent and untransportable genealogies, neglected and often destroyed. The now treacherous access to St Eugène seems to only reaffirm that murky access to the past.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)