Les années d’insouciance, celles de mon enfance, de mon adolescence, et les premières années de ma vie de femme… les premières amours…le premier enfant… Le poids de cette légèreté, de cette beauté, de cette tendresse, de cette inconscience ! Peut-être que cela palpite toujours en moi parce que je n’ai jamais quitté ces images pour toujours, jamais je ne les ai rangées dans un tiroir ou une valise, jamais je n’ai regardé la terre de ma jeunesse en me disant que je n’y serais plus chez moi. La dernière fois que j’en suis partie, je ne savais pas que c’était la dernière fois. J’étais venue de Grèce où j’enseignais au lycée français de Thessalonique. Enceinte de huit mois, incapable de voyager en avion dans l’état où j’étais, j’avais méandré soixante-dix heures à bord de l’Orient-Express qui prenait des allures de diligence, puis j’avais vogué vingt heures sur un paquebot, pour venir, comme une tortue, mettre au monde mon enfant sur mes plages. Je n’imaginais pas qu’un petit venu de mon ventre puisse voir le jour ailleurs que là… Ensuite je suis repartie avec ma fille dans mes bras, c’était l’été, je reviendrais pour Noël. Je ne savais pas que, désormais, je n’aurais plus de maison. Je ne savais pas que ma terre ne serait plus jamais ma terre. (11-12)

The carefree years, those of my childhood, my adolescence, and the first years of womanhood ... first loves ... the first child ... The weight of this lightness, this beauty, this tenderness, this unawareness! Perhaps it still pulsates in me because I never permanently left these images, I never put them away in a drawer or a suitcase, I never looked at the land of my youth while telling myself that I would never again be home. The last time that I left, I didn't know it would be the last time. I had come back from Greece where I was teaching in a French high school in Thessaloniki. Eight-months pregnant, unable to travel by airplane in that state, I had meandered seventy hours aboard the Orient Express that ran at the speed of a stagecoach, and then I wandered twenty hours on a steam ship, so that, like a turtle, I could give birth to my child on my beaches. I couldn't imagine that this child coming from my tummy could ever see the day somewhere other than there... Then I left again with my daughter in my arms, it was summer, I would come back for Christmas. I didn't know that, from then on, I would no longer have a home. I didn't know that my land would never again be my land.

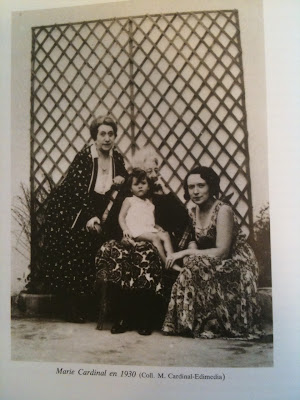

Her lightness of being, her state of carefree existence, came from knowing her home would be there to support her. Once it was gone, she attached herself to the mental image and repeated it throughout her literary career. Les Pieds-Noirs is a photographic coffee-table book mixed with autobiography and history of the Pied-Noir people. It is, in many ways, a reproduction of the lost homeland, a surrogate and horribly insufficient space designed to protect the past from being forgotten.